David Brent Johnson says it’s true, but I find it hard to believe.

Judge for yourself: “I didn’t like jazz when I was a teenager,” Johnson says. “My best friend in grade school and high school was a big fan of it. I used to call him a jazz snob. In fact, when I encountered that term later on, I was like, ‘Hey, I thought I had invented that!’ He would play stuff for me and I would be like, ‘Bah.’”

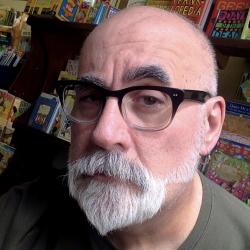

Who’s he trying to kid? It can be argued David Brent Johnson’s is the name most synonymous with jazz in this town. He’s WFIU’s jazz director and host of the shows Just You and Me and Night Lights. His knowledge of jazz artists and recordings is encyclopedic. He was given an imprimatur by none other than local jazz radio legend Joe Bourne back when Johnson was a self-described slacker, spinning discs on community radio WFHB. He knows who the up-and-comers are. He rubs shoulders with current big Bloomington jazz names like Monika Herzig and Rachel Caswell and Janiece Jaffe.

So, where does he get off telling us he said Bah! to jazz?

“I was all into indie rock,” he explains. “I played The Smiths for my jazz friend, and he said, ‘What’s wrong with that Morrissey guy? What’s his problem?’”

A few years later, Johnson started coming around to the jazz side, taking baby steps, mainly because he wanted to seem cool. “It wasn’t until I was in my early 20s. This same best friend, I asked him, ‘What are some good jazz records to buy?’ But I was just being sort of a hipster. I wanted to have four or five jazz records in my collection.

“Around the same time, I also asked this guy named Shawn Pelton who lived in my dorm here in Bloomington, ‘What’s a good first jazz album to buy?’”

The aspiring hipster couldn’t have chosen a better authority. Pelton, a drummer, was tutored by some jazz greats, earning the nickname “Cat Daddy,” and would go on to become internationally known. He now plays for the Saturday Night Live house band.

“Sean had this impish, zen, Monk-meets-Art Blakey kind of vibe going on. He talked like a real hepcat. He looked at me for a moment, and he goes, ‘Miles Davis — “Kind of Blue.” Make love to it, man.’ And then he turned around and walked away — that was it!”

Johnson’s love affair with jazz wouldn’t be consummated just yet. More on that in a bit. Today, he represents a dying breed — the NPR jazz DJ. From the 1970s through the turn of the century, jazz was the soundtrack of public radio. Seemingly every city’s or town’s NPR affiliate was playing John Coltrane or Gerry Mulligan or any of the countless artists in between. Overnights on many NPR stations were almost exclusively devoted to jazz. Then, sometime in the ’90s, as the genre itself appeared to be receding from the public consciousness, public radio became less dependent on Chico Hamilton’s or Sarah Vaughan’s records for its programming.

That trend has missed Bloomington by a mile. “Jazz is at the back of the bus,” Johnson says. “I’m speaking about it at the national level not at the ’FIU level. I feel truly lucky to be doing jazz programming in this town. WFIU has, for at least 40 maybe 50 years, had some kind of weekday afternoon jazz presence, which is extraordinary in this day and age. For the last 20 or 25 years, the push has been very much in the direction of talk and news with musical and cultural programming just kind of seeded in. Musical programming is definitely not a priority anymore at NPR.”

Johnson’s own syndicated jazz program can be heard on 15 stations, including one in Manila, Philippines. Most of them, though, are independent stations, not NPR affiliates.

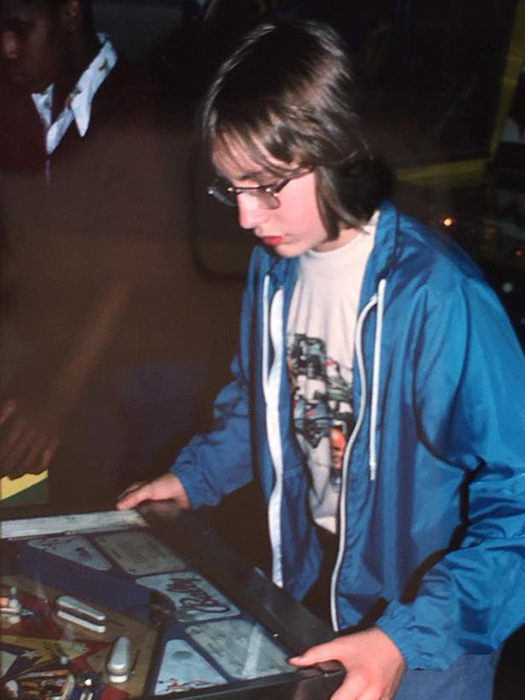

Johnson, playing pinball in the late 1970s, at about the age he caught a bus to Ontario, by himself, “to live off the land.” | Courtesy photo

“I feel very lucky to be at ’FIU because the station invests resources in producing original programming,” he says. “That’s one thing a lot of NPR stations either can’t do or they’re not willing to do. We’ve got the [Jacobs] School of Music here. That’s a huge, huge factor. We would call ’FIU a ‘dinosaur format’ now in public radio. We have a classical/news/jazz mixed format. Most modern-day programming directors would tear their hair out over that — it’s a ’70s/’80s NPR format.”

It works — here. And here is where jazz became David Brent Johnson’s love supreme.

Johnson came to Indiana University with the intention of getting a degree in journalism after graduating from high school in Indianapolis, where he grew up. It didn’t take long for him to chuck the idea of becoming a journalist. “I realized early on I wasn’t cut out to do it. I don’t like making people feel uncomfortable. As a reporter, you can’t be like, ‘Oh, I don’t want to put this bank official on the spot.’”

So Johnson muddled through nearly four years of college, leaving IU a few hours short of a degree, and then took a series of odd jobs. “So by this time I had about a half-dozen jazz albums. One day I was sitting in the Daily Grind, a long-gone coffeehouse in Dunkirk Square — I had actually worked there at one point. I was writing a letter to a friend, and they had music on the overhead speakers. Suddenly, this siren song just pulled me in. It was a Count Basie recording from the late ’30s. It wasn’t even a notable or particularly memorable recording. I went up and asked them what was playing, and they told me, “Now Will You Be Good.” I went right across the street to Streetside Records — that’s gone, too — and they had a Count Basie cassette. The song wasn’t even on it but it covered the same period, 1937 and ’38. Just classic, swinging, vibrant music from the big-band era. It was infectious. There was some kind of joy in the songs. I had this awakening. It was my light on the road to Damascus moment. It was like a religious conversion in a weird way.”

Now he was hooked.

“I went through a period where almost all I listened to was jazz. I was just zealous,” Johnson says. “The music just seemed to match life as I was experiencing it. Still, to this day, it’s so subtle, yet it’s so direct. It’s so creative. It speaks the language of life in a way that I never get tired of.”

Language is another passion in Johnson’s life. A paid talker as well as an inveterate one, he loves to write, even winning a couple of Indiana Society of Professional Journalists awards for his pieces on the arts for the defunct local news weekly Bloomington Independent. He also would write pieces for the national NPR website’s “A Blog Supreme” page — before NPR dropped the page — introducing casual listeners to jazz notables like Nina Simone and Billy Strayhorn and recommending five carefully selected representative songs.

Jazz had whispered in his ear when he was 24 years old and now he whispers to his WFIU listeners. “This is something I think about a lot as a jazz DJ,” Johnson says. “It’s especially easy to fall down a certain kind of rabbit hole and only speak to a narrow slice of the audience.” Here, he adopts a deep, breathy, authoritative voice: “‘As we all know, Dizzy Gillespie’s famous alternate take of “Diggin’ Diz” from 1946, the version that didn’t get released …’ — 95 percent of your listeners are starting to snore. They’re like, ‘Who cares?’

“Part of my mission is to try to pull as many people into the music as I can. Jazz can seem like a daunting thing, a kind of hip, insider, club thing, and I don’t ever want to make people feel like that.”

Johnson knows a thing or two about clubbishness. He was on his school chess team and was one of the class brains. He and a few like-minded pals strove to let the world know how different — how apart — they were. “When I was 12, my friends and I were in this enrichment class. Gifted, basically nerdy, brainy kids. Some of the guys were also on the chess team. We were like little intellectual juvenile delinquents. We were always trying to impress the adults. We’d go to donut shops and talk about Karl Marx. We didn’t really know anything about Karl Marx; we were just trying to weird the adults out.”

(l-r) Johnson stands with local jazz radio legends Joe Bourne and Dick Bishop. | Courtesy photo

At about the same time, Johnson took to heart the message in a novel he’d read a couple of years previously, My Side of the Mountain, by Jean Craighead George. “My parents had bought me the book. It’s about a kid who runs away from home to live off the land in the Catskill Mountains. My mother said, ‘Now, this isn’t going to inspire you to run away from home, is it?’

“I said, ‘No, no, no, no!’ And then, two years later, I did exactly that. One of my friends loaned me a little bit of money for the Greyhound Bus ticket. I was headed to Ontario to live off the land.

“The next day my friend got freaked out when he saw police cars in front of my parents’ house. My parents had no idea where I’d gone. He spilled the beans to them. It took them about eight hours, making a lot of phone calls and doing a lot of work with the police to track me down. I didn’t quite make it. I got caught just a little bit short of the Mackinac Bridge. The police pulled me off the bus at a regular stop around midnight. I’d been away for about 24 hours at that point.

“I remember talking to the policemen at the Cheboygan, Michigan police station at great length about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I was just trying to make them think, ‘What a weird kid!’ They were bemused.”

That weird kid, when he first reached adulthood, sort of, worked in a couple of record stores in his 20s. “I worked at Tracks on Kirkwood in the boom days of the CD era, the mid-90s. Tracks had a small jazz section I was responsible for. I would get in these long conversations with jazz fans. There was a fellow whose dad was a jazz musician. We were talking one day in the alley behind the Runcible Spoon. He said, ‘Have you ever thought about doing a radio show?’

“‘No. I never have.’

“‘I think it’d be a great idea for you to do a jazz radio show.’

“‘Yeah, that would be kinda fun.’

“It just seemed like the most implausible thing. I was working in a record store. I was doing some freelance writing. I was focused on maybe going back to school and getting a library science degree. So another year or so went by and I started working at Borders. I became friends with the husband of a woman who worked there as well. He was a huge music fanatic — all kinds of music.”

Johnson asked the man, named Greg Adams, if he’d be interested in partnering on a sort of Americana music show on WFHB. They’d play jazz, blues, country, folk, covering the years from the 1930s through the ’70s.

To their surprise, WFHB Music Director Jim Manion encouraged them. Manion found a slot for them and they went on the air. Eventually, the two would branch out into their own programs.

“I really got into it,” Johnson says. “I would spend a lot of time putting together shows. I just loved doing it. I loved trying to create narratives. A key moment at WFHB for me was the 80th anniversary of Charlie Parker’s birth. I put together this two-hour special. I found an old interview with Parker. I spliced in interview segments with his music. In the middle of the show I get this call. I answer the phone and this guy on the other end says, ‘Hi, this is Joe Bourne. I just wanted to tell you how much I’m enjoying your Charlie Parker program.’ Joe Bourne, of course, was the legendary jazz DJ at WFIU.

“I went home that night to my wife at the time, Brenda. I burst in the door and I’m like, ‘Brenda! Brenda! Joe Bourne called me up to tell me how much he was enjoying my Charlie Parker show!’ It was like I’d gotten a papal blessing. That just whetted my appetite.”

Johnson’s knowledge of jazz artists and recordings is encyclopedic. | Limestone Post

Oddly enough, Brenda had once asked him what he would do if he could do anything in the world. “I guess,” he told her, “I’d do what Joe Bourne does — but that’s never gonna happen.”

It did. Another WFHB alum, Yaël Ksander, egged him on to pitch a show idea to WFIU. The station was interested but had no spot for him. A couple of years later, Johnson was out in his backyard, mowing the lawn. The phone rang and the answering machine picked up. After he was finished mowing, he checked the machine. “It was a message from Christina Kuzmych, the general manager!” he says. “She said Joe Bourne was going on family leave for a few weeks and they needed somebody to come in and do his show while he was away. Would I be interested in that?”

Johnson jumped into his best clothes and dashed over to WFIU. “It felt like I was walking into hallowed halls,” he says. “It was like being called up to the Cubs and walking into Wrigley Field for the first time. I filled in for Joe while he was out and then he had to go on leave again. They ended up keeping me.”

Sort of a rags-to-riches story. Now and again, one or another of Johnson’s friends who teach at IU will ask him to come in and lecture their classes about how to get a job in radio.

“What on Earth kind of advice can I give anybody?” Johnson asks, rhetorically. “‘Go to school, spend your 20s living a slacker lifestyle, work in restaurants, drink and ingest other substances too much, knock about randomly for a few years, and then kind of stumble into doing something you love. There you go, kids — there’s your career model!’

“I would not recommend my weird, circuitous path to anybody. What I would recommend is, if you find something you love, lock into it and find a way to do it. You can say, like, Joseph Campbell, ‘Follow your bliss.’ There’s truth to that but it doesn’t mean just do whatever you feel like doing because, as my friend Nancy Hiller has written very wisely, doing the things you love involves a lot of hard work and doing a lot of things you don’t love doing.

“But when those little voices go off in your head, when you hear that Count Basie tune in the overhead speakers, listen to it. Follow that light.”