At dusk, the neighborhood at 4th and Rogers streets was quiet. I was quiet, as this is the closest to anything “social” I had been to for months. But what does social even mean with COVID-19? This once bustling arts intersection was also not like itself, much like a rotting log, stagnant on the surface, the only activity being passing traffic and the occasional passerby. But a door on the corner was open. Out of a gray, two-story home was trickly light and voices, hitting up against a white sheet hanging on the porch. On that bedsheet, for all the street to see, was a trapezoidal Instagram Live session, large enough to see something was happening, small enough to realize it was only a fraction.

The soft opening of Abattoir Gallery was livestreamed by both Abattoir and the crews of various performers. Performances were held in one room, with a separate room for the audience. | Photo by Ian Carstens

The first soft opening of Abattoir Gallery, a gallery run by LGBTQ+, Black, and brown folks in Bloomington, occurred on September 25. Like many things born in this pandemic moment, this gallery was originally going to be several things, and pivoting is the name of the game. Gnat Bowden, the lead curator of Abattoir Gallery, said that the night’s performance was going to be in the basement with the audience on the first floor. “You would be able to feel it through the floor,” they said, “but the delay was too disorientating, so we moved it upstairs to a room for performance and a separate room for the audience.” This event was also livestreamed through various means (e.g., the porch bedsheet), both by Abattoir and the crews of various performers. It felt like a transmission from a bunker.

With sporadic nightlights in hallways and a desk lamp sideways on the floor, the matte-black walls sucked in sound and light like that thing Dumbledore carries around. Cords and outlets, beer cans and rolling papers — this was as much a living room as a performance space. This felt special and complicated to be greeted so candidly by the items of someone’s home. The risk was one of hope. A hope to capture that illusive low-fi, punk, back-door-community-feeling aesthetic that can really be felt only in person.

The show itself started casually late. People tucked up their masks to sip from bottles or slip smoke out. I wondered, how would someone perform with a mask, let alone sing? They don’t. I kept my distance, we all did. With the slight suffocation of a cloth mask and the slowly closing ink-black walls, I felt like I had been buried alive. And found myself enjoying it.

Abattoir’s first event included performances by Bloomington band Kleaner, Indianapolis rapper Nagasaki Dirt, and DJ Evan L. | Photo by Ian Carstens

Bloomington band Kleaner, made up of Nia Petrol, Duncan Kissinger, Gnat Bowden, and Reed Brown, set the tone for the evening, kicked the sole desk lamp on the floor, sending up Nosferatu-like shadows on the ceiling. Kleaner sonically smeared my feelings on the wall like butter. They played short morsels, up to two minutes long in a style self-described as that of “Midwest murder ballads.” The sound was tight, concise, if the Australian post-punk band The Birthday Party wrote Scandinavian black metal in Haiku form. And yet the sound was uniquely American in breadth and depth. With a healthy dose of in-your-face, pulling-out-your-hair, momma’s-scolding anger, Kleaner stretched sound like some type of tendon, almost to the point of snapping.

Abattoir Gallery is equally about the negative space between works and performances, providing a much needed social balm. In between sets, the conversations organically drifted along a cloud of smoke — to patriotism, to the American flag. A conversation developed of how, in the “Blue Lives Matter” movement, seemingly self-described super-patriots had remade the American flag into a black and white symbol with a blue line, a point that the Kleaner drummer noted was an ironically disrespectful gesture to the very institution these groups seek to uphold. What can really be a symbol for this country? A country built on foundations of genocide, eradication, and denial? These in-between porch conversations reiterated the significance an inclusive, neighborhood, and safe gallery can have in a community.

Indianapolis rapper Nagasaki Dirt brought us back from the porch for the second set with a sound like the heaviest of Thanksgiving dinners, serving up a multivitamin blend of autotune with live overdub, beats reminiscent of rapper Travis Scott, and a stage presence that pulled us up out of the floor. With a charming tone and candor, let alone tilted black beret, Nagasaki Dirt brought an energy that felt radical in this time of political and pandemic uncertainty. Poignantly, ND dropped “why all my N— gotta go through just to fucking get to it?” I’m not sure more could be said than this artful synthesis of the pandemic and racial crises.

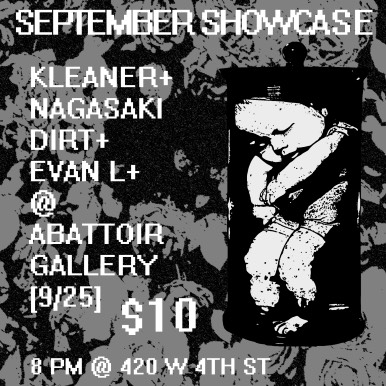

DJ Evan L created the flyer for Abattoir’s first event in September. | Image by Evan L

The night closed with Evan L DJ’ing house bops, dance tunes, and the occasional inverted sound. Evan comes off quiet, calculated, and collected. Yet when Evan isn’t behind the table, he talks to everyone, moving from group to group. Evan also designed the flyer for the night’s show, the virtual means to how we all got here. As I got on my bike to head home at the end of the night, it was Evan’s set bumping out the front door that carried me home.

While this soft opening of the Abattoir Gallery was purely musical performance, Gnat says the gallery will exhibit across mediums while maintaining a safe and secure space for LGBTQ+, Black, and brown people. “All artists will be paid,” Gnat says, and the project will “invest in artists in our community, invest in community futures, and sustain a physical space.” As the pandemic and its factual existence are opposed by some, while people protest in our streets to address systemic racism and police brutality in our country, spaces like Abattoir Gallery are both a godsend and a gadfly. It is no coincidence that this gallery shares a corner with what many consider to be focal point of the local arts scene — especially poignant in an arts community that’s often criticized for being dominated by middle-aged white people. The arts are a significant part of Bloomington’s identity, but it is worth noting the prevalence of white-dominated spaces and historical paradigms of exclusion. Abattoir Gallery is an open door to the streets of Bloomington to challenge its anti-Black, anti-LGTBQ+ realities.

Learn more about Abattoir Gallery at Patreon.com/Abattoirgallery. Future livestreams for Abattoir Gallery events can be found on Instagram.

Gnat Bowden’s artwork will be part of the Paper Pavilions exhibition, which opens January 15 at the FAR Center for Contemporary Arts in Bloomington. Other featured artists will be Carlson Garcia, Samuel Levi Jones, Rachel Kavathe, Claire Krueger, Maddie Miller, Armando Minjarez, Joann Quiñones, and Andrea Stanislav. Read Ian Carsten’s LP article about Paper Pavilions here.