Historians (myself included) don’t predict the future, but it’s a safe bet that “history” will remember Bloomington in 2019 as the year the Farmers’ Market controversy roiled our city.

The presence of sellers who participate in hate groups and the ongoing objections to them have posed high-stakes problems with no easy solutions. The questions are at once existential and practical. What is the purpose of the market? Who does it serve? Who gets to decide? What does “normal” look like in terms of market operations? What should normal look like moving forward — not only for this longstanding institution, but for our community more broadly?

This essay grapples with these dilemmas from the perspectives of women of color who have been at the center of the protests. They are some of the very people who have the most at stake. Yet media reports and city-sponsored forums have not foregrounded their voices enough. This is a major omission, considering that African American, Latinx, and Asian American women have made integral interventions into the debate.

First, though, a recap of the events leading up to the current standstill.

The timeline

On June 4, some 230 community members submitted a letter to the City of Bloomington’s Farmers’ Market Advisory Council, seeking the removal of vendor Schooner Creek Farm (SCF). The letter documented SCF co-owner Sarah Dye’s ties to white supremacist organizations. The co-signers emphasized that Dye’s presence “creates a hostile and unsafe atmosphere for POC [people of color], queer people, people with disabilities, and the Jewish community to attend the market.” They argued that allowing SCF to remain at the market violated federal law because the market participates in U.S. Department of Agriculture programs that “expressly prohibit discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, disability, or age.”

The same day, Black Lives Matter Bloomington (BLM) declared publicly that it had contacted the Advisory Council on June 1 to flag similar concerns. BLM underscored the “disturbing” decision by “Farmers’ Market officials” to call for police intervention to deal with an earlier confrontation between SCF and “non-violent” detractors. Involving police in such scenarios, especially if protestors were “Black people and other People of Color,” was an “intense overreaction and potentially dangerous and fatal.” BLM implored the city to devise its “policies and procedures for handling protest” at the market and to remove vendors “based upon known terrorist or hate speech group affiliation.”

The city did not comply with either request. Market Coordinator Marcia Veldman responded: “To our knowledge, this vendor has not shared these views at the Market.” She added, “The City is constitutionally prohibited from discriminating against someone because of their belief system, no matter how abhorrent those views may be. The City may only intercede if any individual’s actions violate the safety and human rights of others.” On June 17, Mayor John Hamilton announced that SCF would be allowed to remain at the market.

For the worried, this response was insufficient. Indiana University Ph.D. student Abby Ang started No Space for Hate, an organizing vehicle to educate shoppers about SCF’s affiliations. Tensions escalated over the following weeks. Dissenters attended advisory council meetings. The city held a panel discussion on July 11 to hash out the First Amendment ramifications.

When Mayor John Hamilton closed the downtown Farmers’ Market for two weekends last summer, several vendors established the Eastside Farmers’ Market in the Bloomingfoods parking lot on East 3rd Street. Even after the downtown market reopened in August, vendors kept the east-side location open because they wanted an ‘all inclusive’ market. It continues to operate on Saturday mornings.

On July 27, Bloomington Police officers arrested IU faculty member Cara Caddoo for protesting in front of SCF’s booth. Mayor Hamilton closed the market the next two Saturdays, citing “information identifying risks of specific individuals with connections to past white nationalist violence”; on July 31, he held a press conference to defend his decision. The alternative Eastside Farmers’ Market opened during this time and continues to operate.

Mayor Hamilton fielded questions via Facebook Live on August 12 and announced the city’s response on August 13. The market would reopen with “increased” police presence and surveillance cameras to “enhance safety.” Surrounding streets would be blockaded “to create a larger comfort zone.” Volunteer market ambassadors would serve as “visible embodiments of the inclusive spirit.” Rules for “flyering and expression” would be posted. Meanwhile, city officials would consult with local and national “experts to facilitate structured engagement to move our community toward more justice and inclusion.”

Market leadership did not remove SCF.

Outside the market on August 24, a man drove his SUV into a small crowd of Btown Antifa and No Space for Hate members protesting SCF.

Patrick Casey, head of the anti-Semitic, white nationalist American Identity Movement — the rebranded Identity Evropa — visited SCF’s booth at the market on August 31.

The Purple Shirt Brigade (PSB) began challenging SCF in September. On November 11, five members of PSB — including one dressed in an inflatable unicorn costume — were removed from the market by Bloomington Police and issued citations.

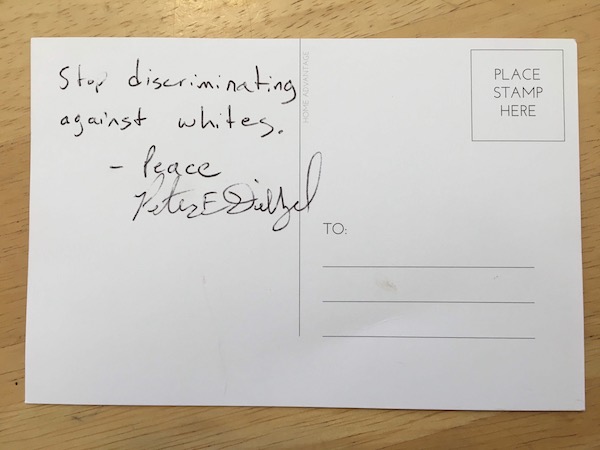

This fall, the Purple Shirt Brigade handed out postcards at the Farmers’ Market for people to write about how white supremacy in the market makes them feel. The cards would be sent to Mayor John Hamilton. This card was signed by ‘Peter E Diezel.’ In April, the Chicago Sun-Times website reported an Indiana man identified as Peter Diezel was associated with Identity Evropa and posted tweets defending Adolf Hitler. | Courtesy photo

On December 10-11, vandals targeted the homes and cars of SCF’s owners, an SCF supporter, journalist Jeremy Hogan, and others.

The issue remains at an impasse. City officials continue to deliberate. The city has not yet made a conclusive decision for the 2020 market season. The Board of Park Commissioners is scheduled to announce a decision at its January 9 meeting.

Looking back, the antiracist and antifascist activists who have worked to air this issue have been stunningly successful. Besides the City of Bloomington, other entities have held multiple community forums to wrestle with it. Countless exchanges among area residents have taken place online and offline, in the open and behind closed doors. Local media — Indiana Public Media, Indiana Daily Student, WFHB, The Bloomingtonian, B Square Beacon, The Herald-Times — have followed this upheaval. It has even appeared on the national radar, ranging from the progressive left (The Nation) to the extreme right (National Vanguard) to the middle-of-the-road (Newsweek) — including the front page of the New York Times, arguably the most influential mainstream U.S. newspaper.

Scattered across the conversations and coverage are the experiences of people of color. What would it mean to place their perspectives at the center of our reflection and think outward from there? To acknowledge them seriously and meaningfully? Might we come away with a fresh understanding of the stakes involved that could prove useful for moving the city past this deadlock?

The interviews

I decided to tackle these queries by talking with a cross-section of women of color who have publicly engaged with the Farmers’ Market predicament. To be sure, “women of color” is in some ways an arbitrary umbrella — the individuals covered by it hail from a range of backgrounds, hold different perspectives, and maintain various relationships to the market and the city. But what became unmistakable after our discussions were distinctive patterns and convergences. Aggregating their stories allows us to see these more sharply.

I chose to focus on women in particular because women of color are almost always simultaneously hypervisible and invisible. Historically, women of color have been especially vulnerable to retaliation, criticism, and violence when they have dared to challenge existing and entrenched configurations of power and authority. In the United States, these arrangements have consistently favored white people. They have also favored men, especially middle- and upper-class, heterosexual white men.

At the same time, efforts by women of color to upend these hierarchies have often been sidelined or even ignored by those around them, observers, and analysts. As a historian, I feel it is important to acknowledge and document their labors.

Just to make clear: This essay is not meant to be a comprehensive exploration of the entire dispute.

The City of Bloomington’s policies are well documented and can be found here. A link to a working draft of the city’s “Rules of Behavior for the Bloomington Community Farmers’ Market,” dated December 6, 2109, is included on its FAQs page. (A “Rules of Behavior” document dated June 27, 2019, was not released to the public until after the arrest of protester Cara Caddoo on July 27, 2019.) Bloomington Community Farmers’ Market Coordinator Marcia Veldman explained her position in two episodes of Indiana Public Media radio shows archived here and here.

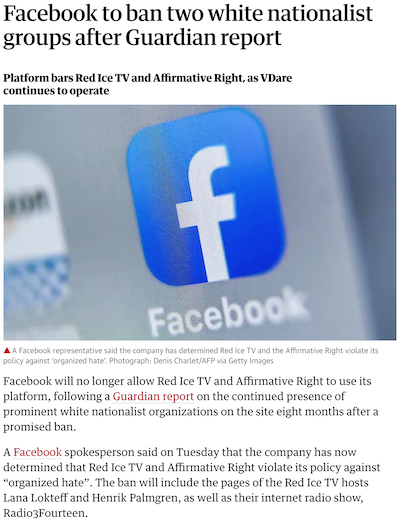

Screenshot of an article on TheGuardian.com reporting that Facebook banned Red Ice TV, a ‘white nationalist group,’ from its platform.

Schooner Creek Farm co-owner Sarah Dye has spoken publicly about her views on multiple occasions. On Fox 59 News in early August, she confirmed she is an “identitarian” but said that “we absolutely reject supremacy in all its forms.” (ADL says “Identitarians reject multiculturalism or pluralism in any form.”) Later that month, Bloomington’s Herald-Times quoted Dye’s confirmation that she is “Volkmom,” the handle she uses for white supremacist online sites and chats. (American Identity Movement leader Patrick Casey leapt to Dye’s defense.) Dye also sat down for an extended interview with Red Ice TV, a prominent white nationalist video news outlet. (In October, YouTube banned Red Ice TV for repeatedly violating its hate speech policies, and Facebook followed suit in November.)

At a Grassroots Conservatives meeting in Ellettsville in September, Dye recounted her turn away from the “liberal-leftist mind-control cult” in 2015 but stressed that “many of my principles have not changed,” especially “pro-environmentalism” and “anti-globalism.” Here it’s worth noting that environmental stewardship has long attracted the far right, including John Tanton, described by historian Carly Goodman as the “guiding force of the contemporary anti-immigration movement.” Organic food has wide appeal among neo-Nazis internationally, and farmers’ markets in some cities have served as recruiting grounds for their cause.

What follows is a distillation of my conversations with eight women of color, edited for clarity and length. Certainly there have been more people of color involved in the protests. I selected a sampling to highlight a mix of vantage points. Of the interviewees, I previously knew half as colleagues, friends, or acquaintances. I found the others through word-of-mouth recommendations. (Note: I did not join in any of the organized protests.)

What’s at stake

Over the course of three months, the testimonies that I gathered, alongside my observations of public discussions and media coverage, amplified several key insights.

First, the risks of this conflict are exceptionally high and potentially lethal for people of color, especially Black and Brown people. Ratcheting up policing in the market and elsewhere in Bloomington should not be a go-to solution. The City of Bloomington’s decision to station more police officers in the Farmers’ Market deters people color from shopping there because it increases the likelihood that people of color will suffer bodily harm.

Second, it is imperative to remember that the vendor in question is but one expression of a vast and organized political white-supremacy groundswell worldwide. Even if this vendor does not return to the Farmers’ Market in 2020, Bloomington’s white-supremacy problem will not be “solved.” In September 2019, the Department of Homeland Security finally named “domestic terrorism,” especially “white supremacist violent extremism,” as a priority threat.

Second, it is imperative to remember that the vendor in question is but one expression of a vast and organized political white-supremacy groundswell worldwide. Even if this vendor does not return to the Farmers’ Market in 2020, Bloomington’s white-supremacy problem will not be “solved.” In September 2019, the Department of Homeland Security finally named “domestic terrorism,” especially “white supremacist violent extremism,” as a priority threat.

In her book Bring the War Home (Harvard, 2018), historian Kathleen Belew tracks the development of the white power movement in the United States between 1975 (the end of U.S. involvement in Vietnam) and 1995 (the year of the Oklahoma City bombing). Belew’s conclusion merits our close attention: “What is inescapably clear from [this] history … is that the lack of public understanding, effective prosecution, and state action left an opening for continued white power activism. The state and public opinion have failed to sufficiently halt white power violence or refute white power belief systems, and failed to present a vision of the future that might address some of the concerns that lie behind its more diffuse, coded, and mainstream manifestations.” The lines between such groups as the American Identity Movement and more overtly violent white power proponents, Belew warns, are “blurry.”

Third, given the proven dangers of white supremacist domestic terrorism, it is frustrating — but not surprising — how city representatives and many local residents insist on framing this issue primarily around First Amendment rights. It would be much more productive to acknowledge the obvious — that freedom of speech is fundamental to our democracy — and then move to an honest and caring assessment about what our community needs to do pro-actively to ensure the safety and well-being of our most vulnerable members. As historian Jennifer Delton argues, “Our constitutional rights are not unchanging abstract principles [but should be] evaluated in terms of their consequences for society at any given historical moment.”

Last August, Black Lives Matter Bloomington published a “Letter to the City Regarding the Farmers Market and Nazi Farmers of Schooner Creek Farm.” In it, BLM stated, “We are confident that the City can exercise creativity in its bid to increase safety at the Bloomington Farmers’ Market.” I heard plenty of creative solutions in my interviews with these eight women. I hope that city leadership and others in our community will listen and be inspired, too.

WU: Let’s start off with some introductions. Who are you? What are you? What drives you?

Abby Ang

ABBY ANG: I am a graduate student at Indiana University’s department of English, currently trying to finish a dissertation on insects in medieval literature. I’ve been heavily involved in activism and electoral politics, mainly starting with Indivisible Bloomington from 2017 to 2019. I am currently on the board for Democracy for Monroe County, am the newly elected vice president of Monroe County National Organization for Women [MCNOW], and am working with Melanie Castillo-Cullather [Asian Cultural Center] and Shruti Rana [MCNOW and Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies] to establish a chapter of the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum here in Bloomington. I convened No Space for Hate Bloomington in late May in response to information about white supremacy at the market.

Jada Bee

JADA BEE: I am on the Core Council for Black Lives Matter B-Town [BLM B-town]. We are currently working on our Black Bail Out Fund and our Make the Right Call campaign that is aimed at helping to move folks away from calling the police for situations that need community engagement and social service organizations, as well as establishing a 311 not connected to police dispatch. I am on the board for Democracy for Monroe County, the progressive political organization in Bloomington.

Additionally, I am a board member and Diversity & Inclusion chair for MidWay Music Festival. We just had our 2019 festival with over 30 acts in various locations in Bloomington, featuring women of all identities and non-binary performers. I am also one of the singers for Royalty Prince Tribute Band, a high-energy seven-piece funk band devoted to performing the works of Prince. Additionally, I just formed a new band called the Negative Piece, a four-piece Black-, queer-, and trans-fueled soul/goth band.

Mónica Billman

MÓNICA BILLMAN: I’m one of the owners of Goldleaf Hydroponics. Goldleaf Hydroponics was established in 2016, and that’s also right around the time that we did our first farmers’ market season. With the opening of our business, we thought it would be a great overlap because we sell everything you need to grow everything indoors and outdoors all year long. We brought a unique set of plants and knowledge to the market — that’s what people expected. A lot of the current farmers’ market vendors are our customers. It’s really cool to see how we come full circle, because we supply them things they need to start their seeds, or nutrients, or anything else that would meet their organic growing needs. It was really cool to be alongside them for those three years, knowing we were all supporting each other in the community, being able to provide them with all the tools that they needed to have their operation going.

Cara Caddoo

CARA CADDOO: I write and teach, mostly about African American history and the media. In terms of work, I split my time between the Media School and the history department at Indiana University–Bloomington. A lot of my research considers our changing ideas about human and civil rights. I also write about protest movements. I’m an immigrant and an adoptee. I was born in South Korea and came to the States when I was about two years old. I grew up in a multiracial and mixed-race family in Bloomington, Minnesota. My husband, who is also from a multiracial and mixed-race family, was born and raised here in Bloomington, Indiana. I guess I’m just destined to be a Bloomingtonian. I think if you care about the people around you, your friends, your family, your neighbors, it just makes sense to do what you can to make things better.

Lauren McCalister

LAUREN McCALISTER: I wear multiple hats in the community of Bloomington. I work at IU. I teach yoga in multiple spaces. I have been a board director of Bloomingfoods. I do a lot of connecting with different groups in terms of urban welfare, thinking about how food systems and sustainability come together with policies and procedures in the city, although I don’t live in Bloomington anymore. I live in Ellettsville now, on our farm, Three Flock Farm.

I’m from Knoxville, Tennessee, originally. I am a Black woman. I came to the state of Indiana to attend St. Mary’s College at Notre Dame. So I’ve had a privileged educational background, in terms of specificity, one-on-one attention, and scholarship. I came to IU to finish my degree in 2010 in political science and English. I continue my education now as a grad student in public health. I’m a lifelong learner, I’m a mother, I’m a sister. I engage with the world from a unique perspective because of my intersectionality but also my education. It’s something that shapes me in the sense that my mother’s generation, all of her brothers and sisters, went to college. That was a huge accomplishment for our community and for my family individually. I think higher education is a space that for me is a frontier of conversation and evolution. College campuses are a place where that change can often be inspired, but we have to take that change into communities around them, so that we can then effect change in rural areas.

I originally came to IU Bloomington to study food deserts at SPEA [IU’s O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs]. I moved to Not-So-Brown County (as I call it) and tried to figure out why the farms there weren’t just feeding the kids in the local schools. Why were we bringing food from different states when there was a farming drought. People weren’t getting enough funding to continue farming and schools weren’t able to provide nutritious food. Why not work together for a mutual goal?

That failed completely. I met my husband [laughs]. We moved to a commune in Not-So-Brown County called Kneadmore. There my husband and I started our farm. We got married, and for our wedding present we asked for sheep and trees and plants to dig deep and find roots in that space. We got three ewes and one lamb, and from there every year we have increased our flock.

Michelle Moyd

MICHELLE MOYD: I am a historian of Africa, and I’m especially interested in African colonial soldiers, World War I, and other histories of armed conflict in Africa. I teach at Indiana University–Bloomington in the department of history. I am also the associate director of the Center for Research on Race and Ethnicity in Society, also at IUB. In this work, I am driven by my desire to have more fairness and access for marginalized people in all spaces, including at the university. I am passionate about language, debunking racist ideas, and deconstructing myths about people of African descent. I am a wife, mom, stepmom, friend, military veteran, and social media warrior. I am an introvert, but I have no problem speaking in public, so I’ve been trying to take more opportunities to share my knowledge with the wider Bloomington community when I can.

Amrita Myers

AMRITA MYERS: Daughter. Sister. Friend. Activist. Teacher. Scholar of African American history. My research focuses on Black women and slavery in the American South. I’m a professor at Indiana University, and I’ve lived in B-town for over fourteen years. My justice work in Bloomington has focused on race and gender inequity, and it’s led me to work with BLM B-town and the Purple Shirt Brigade and to help co-found B-town Justice. I am driven to see justice for Black and Brown people and for women of color, so the overlap between my teaching, my research, and my activism is clear. I got tired with just writing about these issues. Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown’s deaths propelled me out of the classroom and into the streets. I’ve been doing work on campus and in the community ever since, a lot of which tried to build bridges between Bloomington and IU.

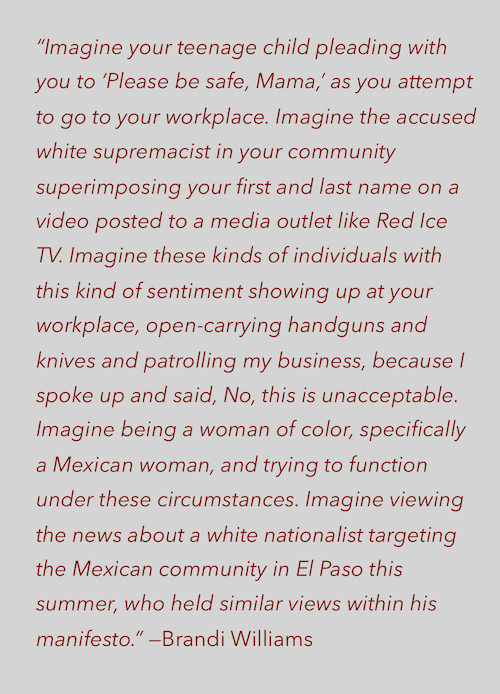

Brandi Williams

BRANDI WILLIAMS: I’m the owner and operator of Primally Inspired Eats. We specialize in authentic handmade, gluten-free, and primal/paleo inspired artisan goods. We’ve been in business since 2015 and initially launched through the Bloomington Community Farmers’ Market. We have a very unique business model in the sense we collaborate locally with Cup & Kettle Tea Shop, renting their kitchen space, and selling our baked goods through their storefront. We also package and sell our products at the local co-op Bloomingfoods, in our online store, as well as at the Eastside Farmers’ Market and Bloomington Winter Farmers’ Market.

Primally Inspired Eats is certainly more than just our business. It really is a manifestation of much of what drives me as a person. Besides spending time as a baker, I’m a self-proclaimed research junkie too, another driving force. I will research the heck out of a topic and make every attempt to immerse myself in it. Nutrition, food, and preventative measures for health and wellness, oh heck yes! Watching my mother experience a health crisis and ultimately losing her at a young age has undeniably become a driving force. Interestingly, that experience ended up stimulating inspiration in the form of health through nutrition, which led to cooking and baking, which led to experimenting with nutrient-dense alternative ingredients, and eventually the launch of Primally Inspired Eats. It’s amazing to me how these life events weave themselves together sometimes.

Teaching has also been equally influential for me. I spent two incredibly informative and inspirational years as a graduate assistant for the EDCI 285 Multiculturalism and Education course at Purdue, teaching the intersectionality of identity, race, class, gender, and sexual orientation to education majors. Tough topics, lots of conversation, reflection, and research. Probably the only other “job,” besides becoming a mother and creating Primally Inspired Eats, that I have had complete love and passion in doing.

Then, for me, there is motherhood, which inspired me to knit all these passions together. How I consciously spend my time, which now focuses very much on my kiddos, health and wellness through food and nutrition, and my need and love for research and teaching. The obvious portion of this tapestry has manifested as Primally Inspired Eats. Primally Inspired allows me to share in the best possible way all the things I’ve learned around alternative and nutrient-dense focused baking. I get to share the results of that research in the form of really delicious and nourishing baked goods. I also get to have very meaningful, informative, and reflective conversations with our customers, around interesting and sometimes even tough topics related to health and wellness, another aspect of our business that I completely adore.

Finally, Primally Inspired also allows for freedom. Freedom for me to choose how I spend my time and, most significantly, for the daily incorporation of the most important human beings in my life — my children, my lifelong love, Justin, and a few dear and valued friends. We work daily as a family to grow our business, learn from one another in the form of homeschooling, and spend as much time as possible exploring and pursuing our passions. Primally Inspired Eats has gratefully allowed for so many of the things that inspire me to intersect and meet in this particular time and in this particular space.

WU: What is your relationship to or investment in Bloomington? Are there particular places, contexts, or situations where you feel really connected or at home? Are there others, perhaps, where you feel like an outsider or even unwelcome?

MICHELLE MOYD: I moved to Bloomington in 2008 straight from Ithaca, New York, where I had finished my Ph.D. at Cornell University. My connection to Bloomington deepened when I met my husband shortly after I moved here. We got married at the Showers Inn with lots of friends and family in attendance. We now have a six-year-old daughter who also grounds us in Bloomington, though she was not born here. In addition, I have an adult stepdaughter who was born in Bloomington and attended IUB for her undergraduate degree. We have a lot of friends here, we own a home, we pay taxes. My husband owns a small business in town. My daughter attends The Project School, takes skating lessons at the Frank Southern arena, and plays in the city’s parks. I care about these spaces and making sure that my daughter has the opportunity to enjoy as much as anyone else. I also care that everybody has the opportunity to enjoy all the things that she does.

The two places in this town where I feel most welcome are the I Fell Building and the Monroe County Public Library. In those spaces, I never question whether I belong.

BRANDI WILLIAMS: We have definitely been invested in Bloomington in the sense that we literally chose it as our place to build community around ourselves and our children. I feel like that’s a pretty sacred thing, to consciously choose the place you call home. It was important for us considering we had grown up in other parts of Indiana that were blatantly exclusive, damagingly conservative, and wholly unhealthy. We thought B-town seemed different, we wanted it to be different, to be the community it claimed to be. After experiencing such a lack of concern from the broader community around this particular issue of white supremacy, I have very much had experiences of feeling unwelcome or like an outsider. I feel very much as though I am simply an inconvenience that won’t quite peacefully go away.

BRANDI WILLIAMS: We have definitely been invested in Bloomington in the sense that we literally chose it as our place to build community around ourselves and our children. I feel like that’s a pretty sacred thing, to consciously choose the place you call home. It was important for us considering we had grown up in other parts of Indiana that were blatantly exclusive, damagingly conservative, and wholly unhealthy. We thought B-town seemed different, we wanted it to be different, to be the community it claimed to be. After experiencing such a lack of concern from the broader community around this particular issue of white supremacy, I have very much had experiences of feeling unwelcome or like an outsider. I feel very much as though I am simply an inconvenience that won’t quite peacefully go away.

MÓNICA BILLMAN: If you go to Goldleaf Hydronponic’s Facebook page, you can see how we’re involved. We set up a lot of hydroponic systems and aquaponic systems in schools. We work very closely with a farm in Ghana to bring in local products like spices and other foreign foods that you can’t get anywhere else. We’re the only supplier in the country. Little things like that make us stand out. I feel like we brought a unique set of plants and knowledge to the market. Anybody that loves plants knows us by now in the community. For us to just not to be at the market, there’s that void there now, that is really sad to not be able to fulfill. The market now being the white supremacist market is leaving a lot of empty holes in different areas, emotionally, physically, in the community.

LAUREN McCALISTER: I’ve known Marcia [Veldman, Farmers’ Market coordinator] since 2010 and on because I was part of the community plot program, where you can rent a garden plot. Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard would help you grow your own food. I’ve been interacting with her and Robin Kitowski [Farmers’ Market Advisory Council member] through the years.

So I’m going to the Farmers’ Market, I’m trading my Bucks [food stamps] in, I’m on EBT [Electronic Benefits Transfer food assistance distribution system], and the Farmers’ Market will double your money to purchase food. I’m all participating in the market in the best possible way. I’m consuming there, I’m building community there. All in. Every Saturday. Enough that if I wasn’t there and I came back the next Saturday, people were like, “Where were you? Is [your son] okay?”

For me, the Farmers’ Market was supposed to be an access point for someone living in poverty, particularly people of color, to participate in our community. It was doing what it was supposed be doing. That’s what I saw as the goal of the market’s Double Bucks program. I thought that even if the market doesn’t make the city money, that’s not the point. The point is that there should be some public spaces that are supported and welcome everyone. Because that’s what my tax dollars pay for, right? … Yes!

JADA BEE: I’m unique out of BLM in that I went to the farmers’ market nearly every weekend, and have since high school. Especially in college because I had white friends, that’s what you do on a Saturday. In college, I had white hippie friends who were interested in sustainability culture and gardening and farming. So I got into it, too. It actually spoke to my Blackness in ways that they didn’t fully realize. Everybody’s grandma has a garden — that’s where you get the majority of your vegetables for the summer. Even if you live in the city or city-adjacent, somebody’s growing tomatoes somewhere. That spoke to me. We used to have a garden. My dad did that because that’s what his mom did.

Black people have been saying since the beginning of this whole thing but also anytime the market is a conversation: That the market is not a Black space, and it’s not a space where Black people feel comfortable. With the market in general, there’s just not been a clear space that says it’s okay for us to be there. It is half a block from the two biggest Black churches in town. People go to the churches all weekend long. And yet you do not see this congregation going to the market, you don’t see it because they don’t feel welcome. I’ve spent a lot of time since all of this recent controversy started, talking to other members of the Black community, some churchgoers, some who go to those two churches in particular, talking to them about why they don’t feel comfortable there.

The bottom line is that they don’t see themselves there. We know from research, and we know from just anecdotal evidence, if we don’t see it, we can’t be it, we don’t want to be there.

And that’s particularly true in intensely small communities. We make up less than 3.6 percent of the population in Bloomington. That feeling of “this is not for us” permeates market culture — and to be real, it permeates Bloomington and even activism in this town.

As far as I know, there are no Black vendors — and if I am mistaken I could be forgiven, seeing as that means there isn’t enough to see or feel. Which is crazy because there’s enough Black farmers and/or vendors in Indiana to form a Black-only farmers’ market in Indianapolis, so one would think [there should be Black sellers at the Bloomington market]. They had to break off from the Indianapolis market as well, because they were having issues of being accepted and included. And so they just decided, instead of trying to make a square hole fit a round peg, that they would just make their own. Black people do this constantly, in our micro-economies, in our culture, in various ways.

There’s a definite feeling among African Americans in Bloomington that the Farmers’ Market is an exclusively white venture of the city. It’s really about representation. Everything is always about representation. When the Nazis were “revealed,” it wasn’t a surprise [to Black people]. Much like when Donald Trump won the White House. Black folks were not crying, we were not shocked. It was like, “Oh yes, of course after the first Black president we’d get the guy who led the birther movement. Yep, that’s how this country works.”

It just seems like a continuation of white supremacy. Nazis are just a violent outbreak symptom of white supremacy.

WU: What inspired you to become involved with the Farmers’ Market situation? How would you characterize your work on this issue? How do you interpret or make sense of how the city and people around Bloomington have responded to the calls to remove Schooner Creek Farm [SCF] and revamp market operations?

LAUREN McCALISTER: I was gifted a loom by this wonderful woman in Not-So-Brown County who just gave me an opportunity. So then when we were getting married, I said, if I have the sheep, I could just spin the wool myself, I could weave whatever I want, I wouldn’t have this high cost, this front load as you start a business, all this overhead. And that’s where I met Sarah Dye. She became a friend when we were weaving together, spinning together, sharing resources. We agreed that living on the land was a gift, that we were just stewarding the animals, the space, and we agreed that working together as women was a vital role in that mission. I find those kinds of women’s spaces very uninhibited. We can agree on some things — that’s really the start of revolution. If we can start agreeing on things, then we can specify what we’re doing here: Why are we in such close community, where can this community go?

I knew nothing about even a gemstone of her thinking that way. [Years later] I started hearing from the rumor mill that she was a Holocaust denier, that the races shouldn’t intermix. She played a video about white supremacy. All third-, secondhand information.

In 2016, a mutual friend comes to me, and says, “Dye tried to recruit me to be in her white supremacy group.” Dye is in homeschool groups that my kids participated in events with. It’s becoming personal, more of a problem. Because now we have complicit behavior by the adults. If this is actually happening, and we aren’t talking to them, family to family, about “Hey, this is what we’re hearing. Is it true? What can we do?” Now I’m participating in her protection, now I’m participating in not sharing that narrative. Inappropriate. I had to do something. Some of us sat down with [our mutual friend], and said, “Listen, if you keep her in this circle, if you keep her around your kids, don’t expect us to be around.”

(l-r) Amrita Myers, Abby Ang, Michelle Moyd, Cara Caddoo.

Everyone was finding out around the same time these accusations, these criticisms, these problems were occurring. [At that time, some friends said], “I’m not going to buy from [Sarah Dye] anymore.” But it still didn’t change the fact that my husband and I were trying to be vendors at this farmers’ market.

Sitting down with Marcia [Veldman] this summer was really revealing. When I spoke with her, she said, “Well, I just didn’t want to throw out false accusations.” Times’s up, time’s up for all that. You know why she didn’t want to throw out any accusations? Because she had no procedure or protocol for that kind of thing to happen. For Marcia not to protect those [other] vendors speaks to her fear of what someone like Sarah [Dye] with those extremist ideas would do to her and this community if they were called out.

And so after two years of the community staying quiet and doing nothing, we fast forward to unicorns at the market. We fast forward to it getting shut down. Eighty thousand dollars a week or however much they’re paying [for] the cops and the barricades. All of that could have been avoided had white people talked to white people about this white person.

Women of color have to get involved because white people aren’t talking to white people about white people — about what they need to do when they find out that extremist views are happening in their community. It’s not just my community. That’s not something we can be complicit in. We can’t pretend as if this information is not dangerous.

And then, then the drama at the market started. Then people started getting scared. Then I stopped going. How can I go? You’ve made it very clear I’m not welcome unless I’m comfortable with cops, unless I’m comfortable with my child asking me why are there barricades everywhere now. And I’m not. That’s not a farmers’ market. We need a new word. Someone hashtag it. I don’t know what this is, but it’s not a farmers’ market. It’s just not something to pretend as if I’m going to normalize, I’m going to pretend like it was this way the whole time. It hasn’t been dangerous to buy vegetables until people remained silent and did nothing to protect each other.

BRANDI WILLIAMS: I became publicly involved when I chose to speak about my concerns early in this season following the release of the “Volkmom” information related to Sarah Dye. I had known these individuals through our homeschooling community, as well as the farmers’ market community for several years. These were the two communities we leaned heavily upon to help build community around our family when we initially chose to stay in Bloomington. We had no family locally so it was important for us to build close and trusted community around ourselves. To be honest, I was completely enamored with both communities, and maybe a little desperate as well. New to town, young child, husband working a lot of hours to pay for a small but newly purchased home, I needed people in a big way. Looking back, I think that is much of what influenced my silence and initial response to my early experiences with each of the farmers.

In 2015 there were two separate instances. One was with Sarah Dye at the Buildings and Trades Park during a homeschooling playgroup. She listened in as I was commenting on a package of propaganda we had both received from a shared friend. It was white supremacist ideology, wrapped in this crunchy, back-to-the-earth kind of package. The whole blood and soil sort of tone. I expressed how problematic it was, why, and that it had been sourced from a site that referred to individuals like myself as mongrels. I did most of the talking. I remember thinking how unsettling this felt. I was seriously wringing my hands about it. It was one of those things where I was also looking for community, and I was a mother, and she seemed very much accepted and embraced by that homeschooling community, the farmers’ market community. These two communities that were sort of my areas of socializing and creating community around myself, she was very much at the center of some of those communities. … I never really talked with anyone after having that experience with her, because it didn’t seem like something that would have been well received in my social circles.

That same summer I had a secondary encounter with her husband, Doug, again at a homeschooling park day. We were at Lower Cascades Park and, in the midst of conversation, he said, “Brandi, you know about Jews right? They are taking over the world and have to be fought against.” Then in response to my bewildered look, he continued, “You don’t understand, they are infested with an alien disease.” He fully believed this. I remember thinking, we didn’t have a lot in common to begin with, I’m done, and just made a mental note. It was another one of those things where it was like, what was I going to say? Who was I going to share this with? In a small town, you’re new, you’re trying to establish yourself, you’re trying to grow your community, you’re trying to parent, all these things.

That same summer I had a secondary encounter with her husband, Doug, again at a homeschooling park day. We were at Lower Cascades Park and, in the midst of conversation, he said, “Brandi, you know about Jews right? They are taking over the world and have to be fought against.” Then in response to my bewildered look, he continued, “You don’t understand, they are infested with an alien disease.” He fully believed this. I remember thinking, we didn’t have a lot in common to begin with, I’m done, and just made a mental note. It was another one of those things where it was like, what was I going to say? Who was I going to share this with? In a small town, you’re new, you’re trying to establish yourself, you’re trying to grow your community, you’re trying to parent, all these things.

I kept reflecting back on these red flag moments, and how I chose to not speak to anyone about my concerns. It just didn’t seem like an option. I intuitively knew then that my concerns, thoughts, and immediate understanding of what they represented would not necessarily be welcomed. It didn’t feel like a safe thing to talk with others about. What did feel safe was to carry on and not draw any more attention to the fact that these things deeply disturbed me, especially as a Brown woman.

Fast forward to present and I knew beyond the early experiences I had in 2015, we could also trace a 2018 altercation at the SCF booth back to activists simply attempting to bring attention to the involvement of SCF with white supremacist groups. As we entered this 2019 market season, the release of the grossly derogatory activities of Volkmom became apparent as well. I first became involved by simply talking to others. Everything that had taken place finally began to spur communication with others in the community. We started hearing back from others who had similar experiences, too. We were talking about it out of necessity. We realized there had been community members who had already experienced intimidation because of trying to speak up years before as well.

This is when we made the choice, my husband and I, that I needed to speak up about our previous encounters. There was clearly a pattern of involvement in an ideology of white nationalism, white supremacy, or what we would later find out they call identitarianism. Pretty much all the same in the sense that their ultimate desire is a 90% all-white ethno-state. Identitarians, I guess, claim they aren’t violent because they stand behind a peaceful removal of nonwhite citizens. That seems laughable, if it didn’t feel so personally dangerous.

The sad part for us is that, once I finally attempted to find my voice around all this and express my concerns and fears, it was met with obvious acceptance and support from those closest to us. But on a larger community level, there was either silence, questioning, minimizing, or simply the old go-to this season, “It’s a First Amendment issue.” The message of “nothing to see here, nothing to be done.” And the worst part, my attempt to speak up resulted in the immediate, insidious, and season-long experiences of intimidation. Of course, none blatant enough to elicit lawful consequences — they’re strategic about that — but it’s plenty enough to frighten you back into silence. So we have tread carefully, continuing to speak with and work with others in our community who are willing to address this issue through an antiracist lens.

JADA BEE: I was first made aware of the issue with SCF when local Antifa reached out to BLM last market season towards the middle or end of 2018. They wanted to inform us of the information about SCF being IE/AIM members for our own safety. I was the only Core Council member who went to the market, and we had other actions on our plates at the time.

This year I personally was interested in efforts to remove SCF. But once the city decided to react to protests by arresting Dr. Caddoo and bringing in more police and more security instead of removing SCF and the Nazis the farm was bringing in, it became apparent that the market was not a safe space for Black people, other POC [people of color], Jewish and Muslim populations, and those in the LGBTQIA community.

I, along with other prominent Black leaders, called for a total boycott of the entire Farmers’ Market, citing the city’s, as well as protest organizations’, care and concern about the commerce of the market over the protection of Black and Brown lives.

I, along with other prominent Black leaders, called for a total boycott of the entire Farmers’ Market, citing the city’s, as well as protest organizations’, care and concern about the commerce of the market over the protection of Black and Brown lives.

Since then, I have continued to advocate for the dismantling of the city’s market and the turning over of the market to the farmers. I have worked with many farmers to talk about the necessity of diversity and inclusion in the process of building the Eastside [Farmers’] Market. And the need to expand any new market to include Black and Brown farmers in the process of becoming a new market. In working with BLM, we have called out the city and mayor directly for the administration’s “MORE COPS WILL SOLVE IT” policy and how detrimental that is to the Black and Brown communities here in Bloomington. We even have a resource list on our website, blm.btown-in.org, about how More Police Does Not Make Us Safer.

MÓNICA BILLMAN: Because we were already so close with our vendors, we already had these connections with them. When this all happened, it was really unsettling that within our own community and small niche of a vendor community there was this disconnect between what they thought to believe would be okay. It’s hard to explain how in the moment when we found out about Schooner Creek’s allegations, we immediately thought, Okay, what do we have to do to make sure we’re safe? A lot of people didn’t see it that way. A lot of people kept justifying the whole situation — they kept being in denial that it was true or just making justifications for it to just kind of go away.

That’s when I kind of stepped in and voiced my opinion toward vendors and the public that this is an issue that goes beyond the market. It affects how everything in the community happens. It’s a much larger national problem the way that minorities are treated just because white people think that it’s okay to be neglectful in a way. So out of a sense of survival is why I became involved.

I kept saying during my talks with the mayor, during the meetings we had with Marcia sand other city officials, this is our place of work for half the year. It’s something that should be taken seriously. Something needs to be done about it. It was really discouraging when literally nothing was being done. They said they had intentions to change the contract to make sure that people like Schooner Creek could not be vendors. But as we’ve seen with the vendors handbook from two years ago, they already changed that because at the time somebody had already found out their beliefs. They added a whole section that vendors should not discriminate against anybody of a different race, ethnicity, gender, disability, etc. So, really, I had no faith that they were going to do anything concrete and practical and set anything in motion to help us out.

MICHELLE MOYD: I have been active on social media. It’s worked out in two ways. One is that people have been very appreciative not just locally but around the country, people who have said, I really appreciate you distilling this and continuing to follow it and posting about it.

The other is that I have engaged in any number of discussions in various Facebook groups or on friends’ pages. I’ve had some really difficult exchanges with people on No Space for Hate and other Bloomington-specific groups. There’s a pattern of, that as soon as you raise the question of racism, people just can’t deal with it. And then it turns into an unproductive exchange.

So those are my two main experiences. One is very positive and feels like I’m performing a useful service to people who want to learn. And the other is just like, “[She’s] part of the rabble-rousing crowd who doesn’t know what’s she’s talking about, there’s nothing wrong with Bloomington, Bloomington is a nice place to be — if you don’t understand that, you’re just an angry Black woman.”

All that free speech stuff gets trotted out, all of the platitudes about why it has to be this way. Why we need to let the neo-Nazi vendor simply continue doing what she does; why certain tactics are more effective than others; the construction of protestors as violent Antifa people who are just hellbent on destroying the market for some irrational reason — as if there’s no basis whatsoever to what we’re pointing out, which is that there’s a neo-Nazi in our market operating freely.

Also the refusal of evidence. This is another really fascinating thing about this moment. Again, it’s not just here but nationwide. There’s clear, excellent research that’s been done to tie all the things up, to show who Sarah Dye is. She’s admitted it herself. Activists have been challenging her presence at the market for quite some time, well before this year’s events. How can one not know at this point who she is and what she stands for? And yet there are people in this town with degrees and intelligence and important offices in city government, white-liberal credentials, who keep using words like “alleged” to describe Sarah Dye’s clear involvement in white nationalist organizations. What is that? How is that possible?

I’m sure our litigious society is part of it. People are very cagey about what they say because they don’t want to get sued, especially if they’re part of the city government. But it’s bizarre to me. People are acting like, “Oh, we just don’t really know.”

I try to synthesize. Definitely over the summer, I was trying to do some synthetic work, to try to tell the story. I post a lot of things that relate to what was going on. If I’m in one of these spaces like No Space For Hate or other group pages, and I see somebody making a ridiculous claim or argument, I often cannot contain myself and I intervene. But of course social media is not the best place for meaningful exchange.

CARA CADDOO: You do contain yourself! So many people have written to me after reading one of your posts, asking who’s that person, her responses are so smart and thoughtful. I haven’t been on social media a lot lately, but I think having these conversations is a really important form of activism. It’s so much labor though.

MICHELLE MOYD: [These] exchanges, it’s very taxing. It does take a lot of work to construct arguments.

WU: The activity and debate around this controversy has largely revolved around whiteness and white people. How do you think the centrality of whiteness has impacted the activity, the debate, and your participation in it?

AMRITA MYERS: Hmm. Are you asking if I ever attended the market? Because, honestly, I never used to go. I felt like it was a “white thing.” Not only were most of the vendors white, so were most of the patrons. It was also very expensive. I never felt welcome there, for a number of reasons. I also feel like much of the debate around removing SCF focusing on First Amendment issues continues to hide the truth of the matter, a truth which centers people who look like me.

Schooner Creek is part of a terrorist organization. Because that’s what Identity Evropa/AmIM is. They support policies of genocide against Black and Brown people. This isn’t a “difference of opinion.” This is about whether or not you choose to support violence with your silence and/or your money. Don’t shop from SCF and you take away the funds that help support that violence. Period.

This is why I got involved in the NSFH [No Space for Hate] boycott, and then moved to work with PSB [Purple Shirt Brigade]. I believe we should support the Eastside Market, and that the city should withdraw from the downtown market and allow it to be run by a growers-directed collective that can ensure that it is a welcoming environment for people of color, religious minorities, LGBTQ folks, and others. More cops do not make Black and Brown people feel safe. This isn’t about free speech. It’s about making sure that those who wish to do me harm aren’t being financially supported and protected by my tax dollars. Civility is a false pretense. SCF isn’t just here to sell vegetables. And I deserve to live.

This is why I got involved in the NSFH [No Space for Hate] boycott, and then moved to work with PSB [Purple Shirt Brigade]. I believe we should support the Eastside Market, and that the city should withdraw from the downtown market and allow it to be run by a growers-directed collective that can ensure that it is a welcoming environment for people of color, religious minorities, LGBTQ folks, and others. More cops do not make Black and Brown people feel safe. This isn’t about free speech. It’s about making sure that those who wish to do me harm aren’t being financially supported and protected by my tax dollars. Civility is a false pretense. SCF isn’t just here to sell vegetables. And I deserve to live.

As we’ve been protesting in the market, the city keeps changing the rules. The more we protest, the rules keep evolving and changing. Like with the signage laws. It was very, very clear that those laws didn’t exist the way they were. They’ve actually been making them up as they go along. As we keep pushing the boundaries, and pushing their buttons, they keep changing the rules. Because we’re basically embarrassing them. And the optics don’t look good for them. We have Marcia on record admitting that these aren’t longstanding signage policies at all.

It’s not about free speech.

CARA CADDOO: It’s about certain people’s free speech. As an historian, it’s been fascinating and troubling to watch how the First Amendment has been reimagined, not just by the courts but also in the news, and in our everyday conversations. I hear terms like “thought police” used to describe certain types of protest and criticism but not others. As an ordinary citizen, if I say, “Hey, that’s racist,” and you, as an ordinary citizen, call me “snowflake,” we’re having a debate, or, I guess, an argument. We’re both using our free speech rights. As long as I’m not threatening or arresting or imprisoning you, and vice versa, neither of us are “policing” the other. So it doesn’t make sense in that context to claim that our rights to free speech have been violated, at least in regard to the Constitution. If my peaceful protest, which I conducted without talking or impeding traffic or blocking commerce, or any of that, was a form of “thought policing,” why was I the one that was arrested?

In any case, I don’t believe our conversations about which vendors should — and should not — participate in the city Farmers’ Market should be framed by the free speech debate. I believe in due process; I believe we should enforce the First Amendment. In terms of the situation here, the city and the Farmers’ Market Advisory Council were presented with evidence that the market’s written rules were broken by a particular vendor with white supremacist ties. I believe if those rules were broken, they should be enforced.

For me, the larger issue that brings all this together is the selective enforcement of the law and “the rules” — some of which are ignored, some of which were created to silence protest. I appreciate that at least one market official has recently admitted that the rules against signage were posted after my arrest even though it’s dated June 27, 2019. [Note: Caddoo was arrested on July 27, 2019], but that admission was made after I was arrested, and after numerous city officials repeatedly told the public for months that I had broken the market’s “longstanding rules.” Actually, I don’t know when that admission first came out. It was never a public apology, or even a personal apology. It happened around the time that I submitted a Public Records [Freedom of Information Act] request asking for documentation of the market’s supposed rules.

ABBY ANG: Collectively, we put a fist through the façade of Bloomington’s “safe and civil city.”

CARA CADDOO: So much of this is about the optics of things.

MICHELLE MOYD: The white liberal insistence on the rules, the insistence on civility, the both sides-ism, the false equivalencies. I’m just done letting people say stuff like that to me without challenge.

CARA CADDOO: The biggest fear, the biggest anxiety, I hear from people who oppose the protesters — besides losing the Farmers’ Market — is being accused of being racist. I think one of the more important steps in moving our conversations forward is shifting the focus away from the fear of being called racist to a real investment in being antiracist.

AMRITA MYERS: Every white person’s biggest fear is being accused of being racist, and they will fight tooth and nail to the death before they acknowledge they have any kind of bias or racism.

ABBY ANG: Bloomington is obsessed with optics, obsessed with optics. If you even look the least bit angry, they’re like, “Oh my God, this person is violent, they’re going attract Antifa.”

They lump a lot of different groups together. They latch on to the media coverage of Antifa nationally, which is not accurate.

Part of this is my precarity as a grad student. I found out that this thing on civility works both ways. It’s very hard to make me look violent. In some ways I have to play that to my advantage, whenever I talk to the media. It’s because I’m a really tiny Asian woman. Sarah [Dye] tried to point toward me to say that Abby is the violent person. That did not stick. I want to acknowledge that this is a kind of privilege.

AMRITA MYERS: It’s about optics, but it’s more than that. This town has built a reputation for itself as being this very progressive, liberal, blue dot in a red sea.

AMRITA MYERS: It’s about optics, but it’s more than that. This town has built a reputation for itself as being this very progressive, liberal, blue dot in a red sea.

ABBY ANG: Blueberry in tomato soup.

AMRITA MYERS: Bloomington is this progressive town, it’s the home of Indiana University, has built its reputation on that. The university is a big part of that. IU and city government work hand in hand to attract Research 1 faculty, to attract endowments, students here. People aren’t going to send their kids to this university if they think this town is being infiltrated by Three Percent militia and the farmers’ market is filled with neo-Nazis. The optics of what has been going on here is a major concern not only to the city but to the administration of the university.

[City and university boosters] are trying to tamp down what’s going on and keep it neutralized because we brought all this ugliness out.

They blame the protestors. They don’t blame Sarah Dye, they don’t blame SCF. They blame us, because we have put everything out into the open. They could have made this go away quickly. The city could have removed itself from the market, they could have done what Nashville and other markets in the state have done. They could have made it a grower-directed, vendor-run, farmers cooperative.

LAUREN McCALISTER: The fact that Not-So-Brown County kicked [Sarah Dye] off the board before we did is embarrassing. Is it that hard? It’s not. Did they apologize? No. They knew what it would do to the economy of Nashville. Even if they aren’t concerned with the safety of Black and Brown people, they made a decision! We remain impenitent.

AMRITA MYERS: John Hamilton and the city didn’t want to be the mayor who lost the market. It is all about optics.

JADA BEE: I have been troubled by the activism around the market. It feels like there is a lot of good information gathering on the Nazis while also dealing with this all in a flippant kind of way. There is a certain amount of whimsy that is happening in the activism that seems recreational, like it’s a social club rather than direct action against the Nazis and the city actions, and that feeds into the whiteness of it. There has been very little Black involvement in the activism surrounding the protests and activism. I personally have been trying to be engaged in conversations with farmers, in conversations with some activists, and have been cut out due to personalities rather than principles.

BLM as an organization took a strong stance against the city’s reaction to the protests, the non-removal of the Nazis, and the over-policing of the market. We gave them simple and easy solutions and engaged in meetings with the city that we thought would be fact finding but instead were merely optics meetings. We said to the city, “You need to fix this, this is a problem, we’re telling you how to fix this, you need to fix this.” Like I said, the city invited us to some meetings, and then stopped inviting us to meetings once we were critical.

[The city] hired a consultant to assess the situation, but never released the data, it hasn’t gotten back to us. [Note: At the December 7 “Considering Our Options” panel, a city representative stated that they had not yet received the report.] It was clear from the data that he was collecting that almost all the Black people he was talking to told him that the City of Bloomington has a major race problem, has a major diversity and inclusion issue. Then we just stopped hearing from them about this work.

None of us have said, “Well, we don’t care, we don’t want to be involved as a group, as an organization.” In fact, I in particular have said the opposite. I’ve said any steps of changing the market needs to have Black involvement, needs to be done with antiracist action, and therefore the anti-Black behavior that is ingrained in all of this [including among activists] needs to stop.

The biggest thing is the boycott. Black leaders in town, myself included, have called for a total and complete boycott of the market, forcing the city’s hand financially. It’s been very interesting to see how Black leaders call for a boycott of the entire market. Much like they did in the Montgomery Bus Boycotts, much like Black folks have historically done in order to achieve success. And that call for a total boycott has been completely ignored by the main protesting organization. They have been pushing a just-boycott SCF, which does not put economic pressure on the city to do anything different. It just puts economic pressure on one vendor who is not the only Nazi vendor in the Bloomington Farmers’ Market. Or the entirety of the problem.

This ignoring of Black leaders and that boycott is in my opinion a very anti-Black behavior. If Black activists are telling the community that we are not safe when you put more cops into the farmers’ market, that that puts our lives at risk. That when you put more surveillance into the farmers’ market, that actually hurts us more. And then refuse to remove the Nazis and allow them to carry weaponry and to walk around the market, these things compound the risk for Black people. The mayor, John Hamilton, in particular does not believe the narrative that more cops make Black people less safe. He rejects that concept outright. As I’ve said, BLM has launched a resource list. Additionally, we just had our Seat at the Table event in order to again combat the ignorance of the mayor, the city, and many activists in the city who continue to use cops as a shield against the white supremacists. The truth is, they will not protect us from the Nazis. BLM is a police abolitionist organization. We believe that the cops do not make us more safe, no matter how black, white, or brown those cops are. It’s just a fact. A full-on fact.

My problem is that if Black people are calling for a boycott, and then the huge chunk of the majority white protestors disregard that, that is the equivalent of walking across the picket line, that is the equivalent of just riding the buses anyways, even though Dr. King called for a total boycott. It’s problematic at best. As for the farmers in this equation, I have talked to some of them directly and I said I know a total boycott will hurt you, but you need to place blame where blame is due. Blame is with the Nazis infiltrating this market and [with] the City of Bloomington admin who act powerless to do anything about it. Farmers should be angry at the city and then force their hands to do something.

If this market would have been completely shut down in May, this would have been solved. Instead, we’ve had an entire summer [and fall] of protests, of people’s labor, of extra costs from the police that taxpayers have to absorb, road closures that have been a pain in the butt for everyone, not to mention the increased presence of Nazis in our community. If Black people would have had the support we were calling for — that’s really where I feel like the anti-Black behavior is happening.

If this market would have been completely shut down in May, this would have been solved. Instead, we’ve had an entire summer [and fall] of protests, of people’s labor, of extra costs from the police that taxpayers have to absorb, road closures that have been a pain in the butt for everyone, not to mention the increased presence of Nazis in our community. If Black people would have had the support we were calling for — that’s really where I feel like the anti-Black behavior is happening.

Yes, the city’s Farmers’ Market is anti-Black because there’s no Black presence within the market, there’s no diversity and inclusion. But then we get into the process of removing Nazis via protest, and Black voices are being silenced and ignored and not supported when they are needed the most in this conversation.

I gave a talk at Seat at the Table, called “Confronting White Supremacy: The Losing Side of White Liberalism and the ‘Negative Peace.’” Dr. King talks about the negative peace, which he calls the absence of justice. It is the perfect metaphor for this Farmers’ Market situation, that the white liberals in Bloomington just want everything to go back to normal. Or if there is protest, it happens in the designated areas where we protest, we don’t speak out of turn, we hand out flyers, we don’t fully boycott because commerce is more important than justice or peoples’ lives. All of this is incrementalism, no change happens at the end of that road, it is a just a tweaking of oppression. We never fully get to justice. We just create new ways to engage in systemic racism and anti-Black behavior.

BRANDI WILLIAMS: I know that when I have attended many of the meetings from this past season addressing the Farmers’ Market issue, it has been starkly apparent the difference in experience, perception, and understanding of the situation, based on whiteness. I have sat with individuals who have gushed about how normal the market is, even with barricades, white nationalists, and weapon-toting supporters of such. Their experience is that they feel welcome regardless. In those very same meetings, I would always feel my cheeks begin to blush, and the tears begin to well, because my experience was the complete opposite. I felt unwelcome as hell. Their whiteness gave them the option of feeling welcome, and because they felt welcome, everything must be normal.

WU: Media — both traditional formats as well as online social platforms — have played a significant role in the unfolding of this issue. What has been the impact of traditional media coverage and social media discussions on shaping the stories and debates about the Farmers’ Market?

CARA CADDOO: A lot of the local media coverage has been preoccupied with a narrow — and very misleading — set of questions about the First Amendment. In doing so, there’s been some pretty egregious mischaracterizations of the protesters’ demands.

ABBY ANG: I talk to reporters almost every week about the Farmers’ Market. I’m hoping that more press helps to put pressure on the city to act. I almost feel as though the PR nightmare that we [No Space For Hate and Purple Shirt Brigade] have sustained has pushed the city to act, rather than any desire to actually work to defend marginalized populations. Maybe I’m cynical. I keep being told that the city can’t solve white nationalism, and I’m frustrated with how the burden often seems to be placed on the community to respond to hate speech with “more speech,” while seeing our speech constantly suppressed.

MICHELLE MOYD: [The Herald-Times] came out pretty early on very clearly about their position. As best as we can tell, the editor and his editorials have been quite clear: He does not see the protest as legitimate, that there’s no problem at the market, and the market is all important and it needs to go back to the way it was. Which means no dissent. Protestors are the problem, the market is sacred.

The editor of the local paper is clearly not on the side of protestors in any way, shape, or form.

But also, I do not have the sense that some of the journalists have an informed understanding of what racism is. They think of themselves as not racist. They do not think they are part of the problem. I’ve had some exchanges online that indicate the pattern I mentioned earlier, where as soon as I ask them to consider what it would mean to be antiracist in this situation, they immediately move to saying “but I’m not a racist,” or some variation thereof. I’m not interested in pinpointing you as a personal racist. I don’t think that matters all that much.

But if you’re going keep bringing it back to you and centering yourself, then I’m going to ask you: What are you doing at your newspaper that is antiracist? And how are your colleagues contributing to antiracist media? I can’t say I’ve had encouraging responses to these questions. They seem to resist that kind of logic, a s if it’s an automatic defensive mode. As soon as you try to point out to them the difference between being a personal kind of overt racist — which is a caricature — and you try get them to think about the structures and their part in it, it’s like they stop listening. You should be able to say, “Oh, everybody has some stuff they need to work on.” To me that’s comforting. But these folks can’t take it. They shut down. It doesn’t just happen here. We’re seeing it in the media across the country. Many journalists do not fundamentally seem to understand their role in a racist society and the structure, and they refuse to do antiracist work. It feels like they’re not even willing to learn what that might entail.

s if it’s an automatic defensive mode. As soon as you try to point out to them the difference between being a personal kind of overt racist — which is a caricature — and you try get them to think about the structures and their part in it, it’s like they stop listening. You should be able to say, “Oh, everybody has some stuff they need to work on.” To me that’s comforting. But these folks can’t take it. They shut down. It doesn’t just happen here. We’re seeing it in the media across the country. Many journalists do not fundamentally seem to understand their role in a racist society and the structure, and they refuse to do antiracist work. It feels like they’re not even willing to learn what that might entail.

I understand there are economics involved — like journalists concerned about losing their jobs. Fair enough, right? But it’s like a script, that as soon as the POC or the person who understands how racism works from experience and/or from years of studying the problem tries to get somebody to talk to them about how one might change, they just can’t. I got called a bully in one of these exchanges. That’s what we’re dealing with, an absolute refusal to hear a woman of color explain what racism means.

It just feels so overwhelming right now to walk into almost every space and see white people perform this innocence, or refusal, or defensiveness. It’s just rampant. It is the structure. We are swimming in an environment that is refusing us.

ABBY ANG: It’s exhausting.

AMRITA MYERS: This whole social media space has been problematic. As much as social media has really been a great space in terms of organizing for activists — it’s been useful for No Space For Hate, for Purple Shirt Brigade, for Black Lives Matter — it is also a really vile space in a lot of ways. The exhaustion factor that we feel having to confront people. The amount of emotional labor that we spend defending ourselves. I stand up for Black people on my page all day long. I’m never going to apologize for that. The number of friends I’ve lost, the number of people I used to go to church with who don’t talk to me anymore. These internet spaces, as amazing as they are, they’re also highly toxic, highly problematic, they’re not safe spaces, they’re totally open, there’s no privacy.

MICHELLE MOYD: Assume that it’s public.

CARA CADDOO: And we should remember that speaking anonymously isn’t the same thing as speaking privately.

I’m not sure that people’s behavior on social media is as separate from the “real world” as we’d like to believe. A lot of people refrain from explicitly stating their racist or sexist or homophobic views publicly. But they still act on those ideas all the time, and women, people of color, we still pay the price. As horrific as online comments can be, it’s harder in a lot of ways to experience unspoken forms of discrimination, and then to have people repeatedly tell you, “Oh, it’s definitely not because of race.”

MICHELLE MOYD: The gaslighting.

(top row, l-r) Abby Ang, Jada Bee, Mónica Billman, Cara Caddoo; (bottom row, l-r) Lauren McCalister, Michelle Moyd, Amrita Myers, Brandi Williams.

WU: How has all of this impacted you — personally, socially, professionally, or otherwise?

MÓNICA BILLMAN: Those months in the summer were so traumatic for us, we would literally wake up Saturday morning thinking, “Okay, this could be our last day here.” Actually, when it reopened, we were asking our friends for bulletproof vests because we thought, what if something like that happened, a shooter was out here. Those are the kinds of scenarios we put ourselves in because we prepared for the worst. And that’s what a lot of people don’t understand. Because they’re white, they never have to think about a Plan B or an exit plan.

I’m not saying most people think that way, but it’s like the message-between-the-lines kind of thing where people think or do or say something that really means like, “Well, sorry we’re not in your favor.” The fact that Marcia didn’t reach out and say, Let’s see what we can do to be better, or, Let’s make sure that our only minority vendors don’t leave the market. It was nothing.

On a side note, I recently received an award by the Commission on Hispanic and Latino Affairs, which I used to serve on five years ago. I was not ecstatic about receiving it. It was really hypocritical. I honestly just threw it away. I was like, this is not an achievement; this is just for show from the city’s officials.

I have a bad taste in my mouth from it all. Because it’s something that’s not resolved as of today. Activist groups like NSFH and other vendors that see the value in fighting for us to be treated fairly, I just think like I’m now more vigilant about where I am, what I do regarding the situation, because unfortunately there are lot of people who still don’t think it’s at all a big deal or something worth still talking about. That’s also discouraging, too.

I have a bad taste in my mouth from it all. Because it’s something that’s not resolved as of today. Activist groups like NSFH and other vendors that see the value in fighting for us to be treated fairly, I just think like I’m now more vigilant about where I am, what I do regarding the situation, because unfortunately there are lot of people who still don’t think it’s at all a big deal or something worth still talking about. That’s also discouraging, too.

We’re losing that financial revenue because we decided not to participate in the market. We’ve pretty much lost all our regular marketgoers who would find us there. We’ve lost the sense of community that we used to feel by the public who would go there to support, because now most people are boycotting the entire market. I totally agree with that notion, because that’s what it’s turned into. The city market is the white supremacist market. That good feeling we get every Saturday morning about going to a communal place and enjoying that time with our family, and meeting other families — it’s taken away a really good thing that we used to have in Bloomington, one of best things in Bloomington.